- Anglo Saxon Christmas Cards

- Anglo Saxon Tribes Of Britain

- Anglo Saxon Christmas Tree

- Anglo Saxon Christianity Beliefs

- Anglo Saxon Christmas Greeting

- Anglo Saxon Christmas Ks2

Julius Caesar led the first Roman invasion of England in 55 BCE, but it wasn’t until 43 CE, under the Emperor Claudius, that a successful invasion brought Britain under Rome’s control as a colony. Roman rule over Britain lasted for more than three hundred years. It was during the Roman period that Christianity first came to Britain: in Book 1, Bede mentions the martyrdom of St. Alban, during the reign of Diocletian (1.7), and the rise of the Pelagian heresy in Britain in the 4th century (1. 10).

The same way in the other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. Anglo-Saxon Christmas The date of Christmas, 25th December, coincided with the Yule festival, so a number of traditions and practises carried over into the new, Christian celebration although, as we saw in Lesson 2, there is quite a bit of uncertainty as to which were originally Pagan and which were. Far from being idle brain-teasers to divert people for half an hour during their lunch break or provide a topic of conversation at Christmas dinner, the riddle, to the Anglo-Saxons, was a serious and enigmatic poetic form, designed to defamiliarise and alienate by depriving a thing of its name or giving an animal a ‘voice’ with which to speak to us. The Vikings and Saxons gave thanks for all of the food they had to survive the winter, thanked Odin, and looked forward to the new year when Spring would make the crops grow again. It also became the date that was chosen to celebrate the birth of Jesus, Christmas, when the Saxons and then the Vikings changed their religion to become Christians.

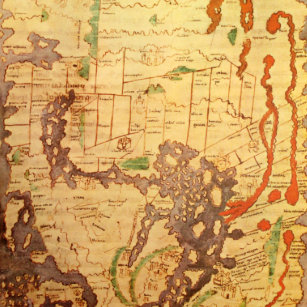

After the collapse of the Roman Empire and the withdrawal of Roman legions from Britain in the fifth century CE, Britain came under increasing pressure from Germanic and Pictish raiders. The Germanic tribes crossed the sea from their homeland in northern Germany, while the Picts crossed the former Roman frontier from what is now Scotland. In the Historia (1.15), Bede discusses the coming of the Germanic tribes—the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes—and their division into separate kingdoms in Britain: Jutish kingdom of Kent; the kingdoms of the West Saxons (Wessex), East Saxons (Essex), and South Saxons (Sussex); and the Anglian kingdoms of the East Angles, Northumbria, and Mercia (including the Middle Angles). There were other minor kingdoms (Bede later mentions Lindsey and the kingdom of the Hwicce, for example), but these seven major kingdoms were the most significant and powerful, and the conflicts between them provide the political context for Bede’s Historia (map).

Because he was born and lived his entire life in Northumbria, that Anglian kingdom north of the Humber is his primary focus for much of the work. Northumbria was originally divided into two kingdoms: Bernicia (extending roughly from the River Forth in the north and the River Tees in the south) and Deira (extending from the Tees to the Humber) (map). Northumbria was briefly unified under Æthelfrith, king of the Bernician dynasty, and again under Edwin, of the Deiran dynasty, who defeated Æthelfrith in battle in 616 CE. After the death of Edwin in 633, the kingdom split again until it was reunited roughly a decade later by Oswiu, the son of Æthelfrith.

Much of this period was marked not only by internecine fighting between the Bernician and Deiran dynasties, but also by the contest for overlordship with the Mercians to the south. Both King Edwin (d. 633) and King Oswald (d. 642) were killed in battle with Penda, the powerful pagan king of Mercia. With his defeat of Penda at the Battle of Winwaed in 655, Oswiu of Northumbria established himself as the most powerful of the Anglo-Saxon kings. Penda’s death marked the end of pagan rule in Mercia.

Bede records that in the period of upheaval after the departure of the Romans from Britain, a Christian mission under St. Germanus came to Britain to combat the Pelagian heresy (1.17–21). But little could be done to stem the tide of the Anglo-Saxon invasion, which brought with it the pagan worship of the Germanic gods Woden and Thunor. The Britons who remained Christian looked westward to Ireland, where a bishopric was established in the fifth century under Palladius (1.13). Irish Christianity developed a number of traditions independent of Rome—notably, the method of calculating the date of Easter—that would put it at odds with the Roman Christianity that took hold among the Anglo-Saxons a century and a half later. Thus, when Augustine’s mission arrived in Kent in 595, it faced the challenge of overcoming both Anglo-Saxon paganism and British (Irish) Christianity. With the exception of a story about King Edwin’s chief pagan priest Coifi (2.13), little attention is given to the pagan religion. Bede considered the conflict with the British Christians over the date of Easter a much more serious issue.

Anglo Saxon Christmas Cards

Anglo Saxon Tribes Of Britain

At the same time, Bede recognized and appreciated the importance of the Irish for the establishment of the Church in his native Northumbria. After the death of Edwin, Northumbria’s first Christian king, the Northumbrian church fell into disarray—its bishop, Paulinus, fled to Kent—until Oswald brought in Aidan, a monk from the Irish monastery of Iona, to reintroduce Christianity to Northumbria. Aidan’s abbey on the island of Lindisfarne became an important center of missionary activity and of learning. The scriptorium at Lindisfarne produced the magnificent Lindisfarne Gospels in the early eighth century.

Anglo Saxon Christmas Tree

The illumination of the Lindisfarne Gospels shows the strong influence of Celtic art. At the same time, it has been suggested that the Codex Amiatinus, produced at Bede’s monastery at Jarrow, exhibits the influence of Coptic art from Egypt (Mayr-Harting 1972, 155). That communities on the isolated Northumbrian coast could exhibit such diverse influences demonstrates the international nature of the Church, and the importance of trade and communication between distant parts of the Christian world. It is no coincidence that many of the most important monasteries were founded on the coast, near good harbors and landing places that facilitated trade.

Although the conversion of the rulers of Anglo-Saxon England took place fairly rapidly between Augustine’s arrival in Kent in 597 and the conversion of Wessex and the Isle of Wight roughly a century later, it must be assumed that pagan beliefs and practices persisted among the common people. For example, although Æthelbert of Kent converted to Christianity in 597, in 640 Eorcenberht of Kent found it necessary to order the destruction of pagan idols. At the same time, there was an adaptation of some elements of paganism to a new Christian context. This kind of syncretism was encouraged by Gregory the Great, the pope who sent Augustine to Britain. In a letter to Mellitus, a member of Augustine’s mission, Gregory encourages Mellitus to convert pagan temples into churches, and to adapt some pagan rituals, such as animal sacrifices, to Christian purposes: “Thus while some outward rejoicings are preserved, they will be able to share more easily in inward rejoicings” (HE 1.30; trans. Colgrave and Mynors). Syncretism was a tool for weaning the English people from paganism.

The Church and the Anglo-Saxon kingship became mutually supporting institutions. It was through a dynastic marriage between Edwin of Northumbria and the daughter of Æthelbert of Kent that Northumbria was initially converted to Christianity. The Church brought with it a hierarchy of leadership, a developing monastic and episcopal infrastructure, and international connections that secular rulers could leverage to support and extend their own power. Christianity became a unifying force in Britain.

Anglo Saxon Christianity Beliefs

Anglo Saxon Christmas Greeting

Discussing the importance of monasticism—and especially of convents founded for aristocratic women—Henrietta Leyser writes: “In exactly which ways their communities helped to consolidate both the newly emergent kingdoms and the new faith may even now not be fully understood, but it is abundantly clear that the contribution of royal women, both as abbesses and mothers—and often as both—was crucial” (Leyser 2016, 19). She cites the example of Seaxburh, the daughter of King Anna of East Anglia and widow of Eorcenberht of Kent (d. 664)—the king who demanded the destruction of pagan idols. Her daughter Eorcengota was a nun in the community of Faremoutiers in Gaul. Her sister Æthelthryth, though married to King Ecgfirth of Northumbria, refused to consummate her marriage, and retired to the monastery at Ely. Her sons with Eorcenberht, Ecgberht and Hlothhere, succeeded their father as kings of Kent; her daughter Eormenhild married Wulfhere, the first Christian king of Mercia (and after his death followed her aunt Æthelthryth and her mother Seaxburh as abbess of Ely). The example of Seaxburh suggests how dynastic marriages and political alliances went hand-in-hand with the spread of Christianity in England.

Anglo Saxon Christmas Ks2

Ely, of which Æthelthryth was the founding abbess, was a double monastery—a monastery with separate accommodations for women and men, and headed by an abbess. Double monasteries were a distinctive feature of monasticism in Gaul, which inspired the establishment of the institution in Anglo-Saxon England. In the selections from the Historia collected here, we will encounter four double monasteries and their abbesses: Hild’s Whitby (Streanaeshalch), Æthelthryth’s Ely, Æthelburh’s Barking, and Æbbe’s ill-fated Coldingham. Bede saw the fire that destroyed Coldingham as evidence of the immorality that was bred when men and women shared the same house, and, indeed, the foundation of new double monasteries was forbidden by the Second Council of Nicaea in 787 because living together in a double monastery “becomes a cause of scandal and a stumbling block for ordinary folk” (Canon 20).